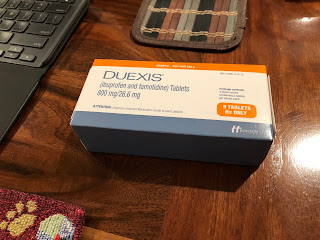

Meet Duexis, a product of Horizon Pharma. Duexis consists of 800 mg of ibuprofen, and 26.6 mg of famotidine. Ibuprofen was patented in the UK in 1961, and expired in 1984; the US patent (3769425A) was granted in 1970, and would have expired in 1987. Originally sold under the trade name of Pepcid, famotidine has been off patent for 20 years, with generics appearing in 2001.

I checked at Sam's Club, and 200 count 20mg famotidine is currently $8.76, and 1,200 200 mg ibuprofen is available for $10.88. Assuming I take three 800 mg ibuprofen doses daily and three of the 20 mg famotidine, that would mean the latter is the limiting factor, and I could go about two months (66 days, plus two doses the next) on that. (The 1,200 ibuprofen would take me 100 days, a little over three months.)

A one month prescription of Duexis (30 days @ 3x/day) is $2,715 (per the Sam's Club pharmacy). Two months is $5,430.

Duexis is covered by US patent 8,501,228, which I assume is the reason for this insane pricing. (Horizon also granted Par Pharmaceutical a license to make a generic starting in 2023 as a result of a patent suit settlement.) This kind of apparently frivolous patent grant is disturbingly common:

When the patent reaches its expiry date, the comfortable monopoly evaporates, replaced by cut-throat competition. Incumbents have three ways of defending themselves. Marketing can create brand-specific demand, dulling the temptation to switch to low-price products. Ibuprofen illustrates this. Developed by the chemists at Boots itself in the 1960s, the patent expired in 1984. But a year earlier Boots had created Nurofen, branded ibuprofen. The clever mix of packaging and advertising protected its profits. The lucrative Nurofen brand was sold in 2006; Boots still stocks the product, which costs five times more than its generic equivalent.A third approach is to "pay the makers of generics not to compete". None of these are in the customer's interest.

A second strategy nudges customers towards newer drugs that are still protected by patent. Omeprazole, a drug to reduce stomach acid developed by AstraZeneca in the 1980s, shows how it works. Branded as Losec in Britain and Prilosec in America, it became one of the world’s bestselling drugs in the mid-1990s. With the patent set to expire in 2001 AstraZeneca faced a drop in profits. So the company took its drug and adapted it, creating a closely related compound, esomeprazole, which it sold as Nexium. Though a clear offshoot of the original medicine, this counted as a new drug and was given a patent. A big marketing campaign and attractive pricing helped shift demand away from Losec and towards Nexium. With the help of this strategy, sales between 2006 and 2013 amounted to almost $40 billion.

Ironically, the surgeon pointed me at a manufacturer program that was going to cut me a break if I used their particular pharmacy — oh, joy! — I only have to pay a $10 copay! But this made me wonder if my insurance was going to pay it or some part of it. In which case, am I not indirectly paying for this usuriousness?

No comments:

Post a Comment